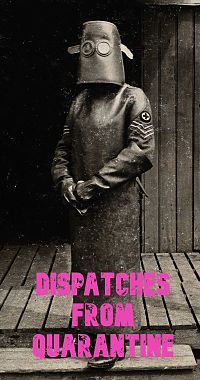

This story is part of a package on the one-year anniversary of the COVID-19 lockdown.

The first time I came to New York, Broadway was dark. Pitch black, in fact. It was Aug. 14, 2003 and that afternoon, much of the Northeastern United States and Toronto had been rendered powerless by one of the biggest electrical outages in history.

The first time I came to New York, Broadway was dark. Pitch black, in fact. It was Aug. 14, 2003 and that afternoon, much of the Northeastern United States and Toronto had been rendered powerless by one of the biggest electrical outages in history.

A few hours later, after an uncinematic cab ride from JFK, my parents and I arrived at the Marriott Marquis in Times Square and were greeted by a scene of tourists in disarray. As a result of a failed backup generator, and in order to prevent falls or heart attacks from climbing 40-plus flights of stairs, the hotel had evacuated thousands of guests to its driveway between 45th and 46th streets. It was packed, and so we were forced to wait out our next move around the corner in Shubert Alley, the famed pedestrian walkway and unofficial heart of the Theatre District.

Sitting on the ground, I leaned my back against our luggage, staring at the Shubert Theatre. Having avidly absorbed that year’s Tony awards, I knew that on a normal Thursday, the latest revival of Gypsy would have been playing to a full house just inside. That night, however, the only thing for a theatre fan to fawn over was the iconic row of Broadway posters displayed on the exterior wall. The lack of illumination meant I could hardly make out the marquee. But for a 9-year-old who insisted on packing a laminated binder for Playbills in her suitcase, the Great White Way had lost none of its luster.

Seventeen years later, on Oct. 5, 2020, I cut around that same corner on the back of a CitiBike, no longer simply a fan but now an Equity card-carrying theatre actor. Earlier that morning, the Broadway League announced that its theatres (and likely most of the city’s Off- and Off-Off-Broadway spaces) would remain dark through May 31, 2021, confirming what those of us in the industry had already come to accept would be more than a year-long absence, if not longer still. Even in normal times, late afternoon on a Monday tends to be quiet in the Theatre District, but now it felt less like I was witnessing a brief moment of respite in an otherwise lively jungle and more like a forest after a fire: ravaged, stark, silenced.

Over the past 11 months, whenever I’ve discussed the state of live performance with people outside the industry, I’m met with looks of pity and concern. They ask me if there’s any work on the horizon. I say no. I try to shift their focus away from actors, explaining the breadth of jobs encompassed in the term “arts worker,” and then feel pangs of guilt as I begin to name them—sound designers, dressers, choreographers, stage managers, box office staff, playwrights—suddenly realizing how impossible it is to account for all the livelihoods that hang in the balance.

“That must be so hard,” they say, these well-meaning friends and acquaintances. “I’m so sorry.” And they’re right. As the days go by, more of us will be without health insurance and financial security, more of our colleagues will leave their dreams behind for good, not because they lack dedication or talent but because the Trump administration lacked any competent or coherent response to the virus and this country has long neglected substantive support for the arts.

Still, there’s part of me that wonders why these same friends and acquaintances aren’t equally as sorry for themselves. Every day the theatre is dark, an opportunity for transformation is lost—yes, for the performers, remaking themselves so completely that, on the best of days, they lack any tether to the real world. But just as importantly, for the audiences who find that bearing witness to those performances, has remade them just the same.

❦

Ever since middle school, whenever I do a play in a new theatre, I practice a kind of sacred ritual. Whether it’s the Delacorte in Central Park or my college black box or one of the Broadway theatres I’ve been lucky enough to work in, the first time I step onstage, I take in the view of the house, the rafters above, and I visualize all the actors who have inhabited the space before. Floating around all at once, in multiple parallel universes, I see them doing their show, oblivious to one another and to me. An Odets hothead waves his fist as three Dreamgirls hit center spotlight. Down left, a Mary Tyrone in white slumps in her chair and a Lady in Red breaks the fourth wall, while all around them, an ensemble of 14 forms the shape of a Seurat painting.

On the day the shutdown was extended for the third time, I found myself summoning specters yet again, but from outside the building instead of in, and thinking this time not of what was onstage in the past, but who, in another life, might be in the seats now. Pedaling down 45th Street, I conjured the lost crowds of 2020 and 2021, filing through the doors of the Booth or the Music Box, each chirp of an usher’s ticket scanner signaling an individual metamorphosis about to occur. I imagined those same audience members emerging a few hours later, each of their experiences radiating outward, creating a ripple effect that is not only personal but political, societal, systemic. And then I pulled back the lens of my fantasy, zooming further out from my spot in the center of Midtown to include all of the theatres, across all of the country, each with its own glimmering sphere of influence.

Of course, the current map of the United States looks exactly the opposite; where there were once north stars, now there are only black holes. And this should be just as terrifying to the rest of the population as it is to arts workers without jobs. Not only because of the important role our industry plays in the larger economy, but because darkness isn’t neutral. It is an absence. The absence of light. The absence of the very thing without which we cannot see—see ourselves, our friends, our families, our past, even our future.

Advocating for financial relief for the performing arts should not be an act of generosity. It is, in fact, one of the most self-serving things a person, or a society, can do. A thriving theatrical landscape is not merely additive. It is the baseline from which we each evolve and we all move forward. Even for those who haven’t seen a play since elementary school, the theatre has, by proxy and without their knowing, illuminated some part of their lives, like the beam of an unseen lighthouse, far away on the shore.

To be clear, the American theatre is nowhere near perfect. Whatever education or escape it can offer is also muddied by myriad inequalities that must be urgently addressed. There are so many deep-rooted, intertwining issues, from commercialization to racism to inadequate wages, that the idea of trying to fix them at the same time as rebuilding a shattered arts economy can feel impossible. But if we can’t return, we won’t have the chance to try, and we simply cannot do it alone.

❦

Unsurprisingly for two communities built on resilience, New York City and its theatres got back on their feet quickly after the 2003 power outage. Just one night after my date with Shubert Alley, I found myself at the Richard Rogers Theatre for my very first Broadway show. Standing in the TKTS line a few hours earlier, I had thrown a minor fit that we weren’t seeing Beauty & the Beast. However, my mother insisted on the Twyla Tharp and Billy Joel musical Movin’ Out, setting into motion a long pattern of my parents curating unusual if not highly inappropriate theatre experiences for their only daughter (case in point: my attendance as the youngest audience member at the 2005 revival of Glengarry Glen Ross, and subsequent obsession with recreating Alan Alda’s performance to anyone who would listen—complete with all the curse words).

As an actor myself, I now understand how unrelenting eight shows a week can be, and that the cast of Movin’ Out likely shed few tears over their unexpected day off the previous evening. And yet, regardless of my romantic childhood notions, I am certain there was a certain poignancy crackling in the air that night. Perhaps it was the result of a little extra rest for some of the city’s hardest-working dancers. But I really do believe that everyone, both onstage and off, was feeling the electricity of live theatre more keenly than before.

This is what I remember whenever I get overwhelmingly anxious or just very sad about the state of the performing arts. I channel what my 9-year-old self felt that night, and how much more powerful our return will be this time around. Because back then, we were really just appreciating the same thing we always do when we come to the theatre: the communion between artist and audience as it manifests at each unique performance. But 2020 has pulled the plug on the existence of that relationship all together. Thrust into a prolonged, unseeing night, our newly heightened senses have been forced to realize that the most delicate, sacred part of the theatre will no longer be its liveness but rather that it is alive at all.

In the meantime, however, there is one light that has survived our now 11-month blackout, something even 24 hours of darkness in 2003 could not keep ablaze: the ghost light. For those unaware of the tradition, this is a floor lamp that remains burning onstage whenever a theatre is not in immediate use. Superstition says it protects the theatre from the many ghosts that haunt its chambers. These days, I like to think of it as doing the opposite. I sit on my couch and perform my middle school ritual from far away, picturing each theatre with its single bulbed lantern centerstage and all of our ghosts dancing around it—no longer past performers but instead the spirit of every artist and audience member currently kept apart, their union protected by its small but constant glow.

Francesca Carpanini made her Broadway debut in The Little Foxes with Laura Linney and Cynthia Nixon. While still a student at Juilliard, she starred alongside Sam Waterston in Shakespeare in the Park’s production of The Tempest. Other theatre credits include Dead Poets Society at Classic Stage Company. If you were moved by this piece, please consider supporting the work of Be An #ArtsHero.

"now" - Google News

March 12, 2021 at 02:19AM

https://ift.tt/3vnL6HJ

We Are All Theatre Ghosts Now, But Poised to Return - American Theatre

"now" - Google News

https://ift.tt/35sfxPY

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "We Are All Theatre Ghosts Now, But Poised to Return - American Theatre"

Post a Comment